A History from the Director, Benay Rubenstein

Benay explains how her history running college in prison programs led to the creation of College Initiative in New York City and College Initiative Upstate in Tompkins County, NY.

In 1983, when I first walked into FCI Otisville and Otisville State Prison as the administrator of a Marist College degree program, I could not have imagined the life-changing education that I would receive from the hundreds of highly motivated, inspiring men and women I would meet inside. Throughout my years spent working with these programs, I came to understand that higher education in prison and after prison is an elixir that nurtures far-reaching intellectual and personal transformation, with ripple effects that touch all of us. I also could not have foreseen that the years working “inside” during the 80s and 90s would put me smack in the middle of unprecedented growth of the prison industrial complex, where I experienced firsthand the deep damage incarceration imposes both on individuals and the core-values of our democracy. [i]

Vivid moments that marked the imminent changes to the carceral system include the day in the mid-1980s when the Education Director at FCI Otisville called me into her office to show me a memo from Washington DC, which predicted that by 1990, there would be 1 million people incarcerated. At the time, there were 439,000 incarcerated persons throughout the U.S. Soon afterward, the mission statement that had been prominently displayed in the front lobby disappeared because “rehabilitation” was no longer part of the bureau’s mission. And, without a doubt, the saddest day of all was the day in 1994 when Congress passed, and President Clinton signed, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-322), which, among other things, made prisoners ineligible for the Federal Pell Grants that supported college in prison. Shortly afterward, NYS Governor Pataki eliminated the use of TAP grant funding for higher education in prison. That was it. Without public funding, 350 college programs in prisons closed overnight. [ii]

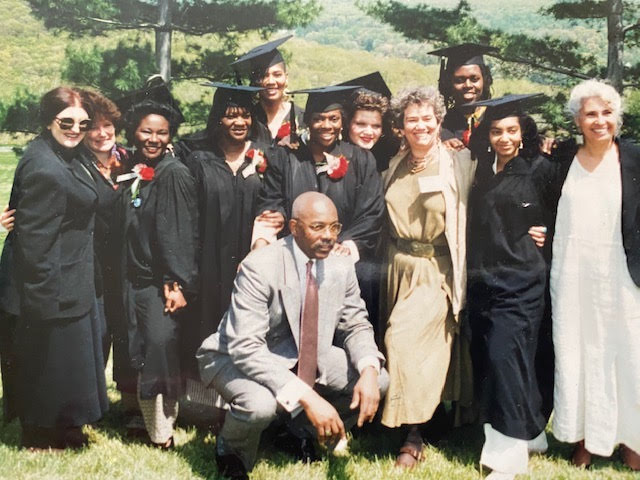

In 1995, shortly after public funding ended, I was invited to be the Coordinator of College Bound at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, NYS’s only maximum-security prison for women. This was one of the first private college programs to return after the elimination of public funding. College Bound was tremendously successful, and within three years, one third of the 650 women at BHCF were enrolled. I still have a clear image of women who had just passed their GEDs running into the college office and waving their certificates, ready to enroll. In fact, the college community at Bedford Hills was so engaging that occasionally there were students who did not want to leave if their release date arrived in the middle of the semester, or if going home would jeopardize their ability to complete their bachelor’s degree. They would laughingly call BHCF the most residential college in the country. However, there was clearly a real fear faced by students who wanted to continue their college education after being released but had no idea where to begin. Finally, in 2000, I decided to move to NYC (where most of the women at Bedford would be returning) to find a way to support women and men released to the City who wanted to begin or continue college.

College Initiative (CI): I started College Initiative in 2002 with the help of two key people: Stephen Chinlund, Executive Director of Episcopal Social Services (ESS) who offered CI a space at ESS in Manhattan, and Charlene Griffin, a young woman who had grown up in prison visiting rooms and became the heart of CI for the next decade. Our mission was to help formerly incarcerated men and women prepare for, enroll, and succeed in college[iii]. From day one, we worked in close collaboration with all of the colleges and universities at the City University of New York (CUNY) and CUNY’s Black Male Initiative. CI quickly attracted remarkable students, many of whom had served long sentences and were ready to begin or continue their college education. Their academic achievements and social activism broke barriers [iv] as students opened their own reentry programs, began teaching at colleges and universities, and practicing law. Today, CI has helped over 1400 criminal justice involved men and women enroll in college and is part of The Institute for Justice and Opportunity at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. [v]

College Initiative Upstate: In 2015, after moving to Ithaca, I wanted to see if there was a need for College Initiative’s work in Upstate NY. As I inquired, I kept hearing about OAR, a non-profit founded in 1977 to protect the civil liberties of those incarcerated in the Tompkins County Jail. I sought out Deb Dietrich, the Executive Director of OAR, who was immediately intrigued and offered me a space in their office. Working together, we quickly discovered that the need for people with justice experience to create new life opportunities through higher education was just as strong in Tompkins County as it was in NYC. In short, it made sense to adapt CI’s urban model to meet the needs of rural Upstate NY. In Fall 2016, College Initiative became College Initiative Upstate (CIU), a new program of OAR. CIU is now a successful program working at the crossroads of higher education and the criminal legal system of Tompkins County. We are well integrated into Tompkins County with 150+ students who have enrolled in either College Prep or a college degree program. We have also recently launched a Peer Leadership group, Voices That Must Be Heard, to nurture emerging leaders as they work for progressive change around issues that have directly impacted them. CIU students are succeeding in college and rebuilding their lives and potential as individuals, family members, informed citizens, and community leaders. Their successes are significant contributors to the dramatic fall in recidivism and incarceration in Tompkins County.

Looking back at my journey, I feel deeply privileged to have been able to walk into the secret spaces our society built at great expense to all of us. There are no words that adequately sum up my experience and I often had to resort to the metaphor “a tempest in a teapot” to explain my day. Yet, the classroom remained an oasis in that tempest: a space where prisoners became students, a place where there was no inside and outside, just men and women learning together and sharing their common humanity.

In recent years, working in the Upstate NY community with students who have faced collisions with the law, addiction and poverty- the classroom remains an oasis, a place where new worlds and new possibility reside.

In closing, I give my heartfelt gratitude to all the people I’ve met along the way, those who became students, friends, and allies, as well as those who remained skeptical of the work that can uplift and unite us. My deepest appreciation goes to my children for who they are in the world, and to my grandchildren and yours, may they find a way to spend their lives doing something they love, something that will uplift others and keep our precious planet spinning.

[i] To learn more about mass incarceration, read Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020 by the Prison Policy Initiative.

[ii] To learn more about the impact of college at BHCF in the late nineties, read Changing Minds: Collaborative Research by The Graduate Center of the City University of New York & Women in Prison at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility. You can also watch The Last Graduation, a film that Barbara Zahm and I made about the rise and fall of college programs in NYS prisons.

[iii] To meet CI students in the early days, watch Reimagine the Future.

[iv] To learn more about barriers to college admissions for applicants with criminal records you can watch Passport to the Future here.

[v] To learn about Susan Sturm’s groundbreaking research documenting CI as a catalyst linking individual and systemic change, read Building Pathways of Possibility from Criminal Justice to College.